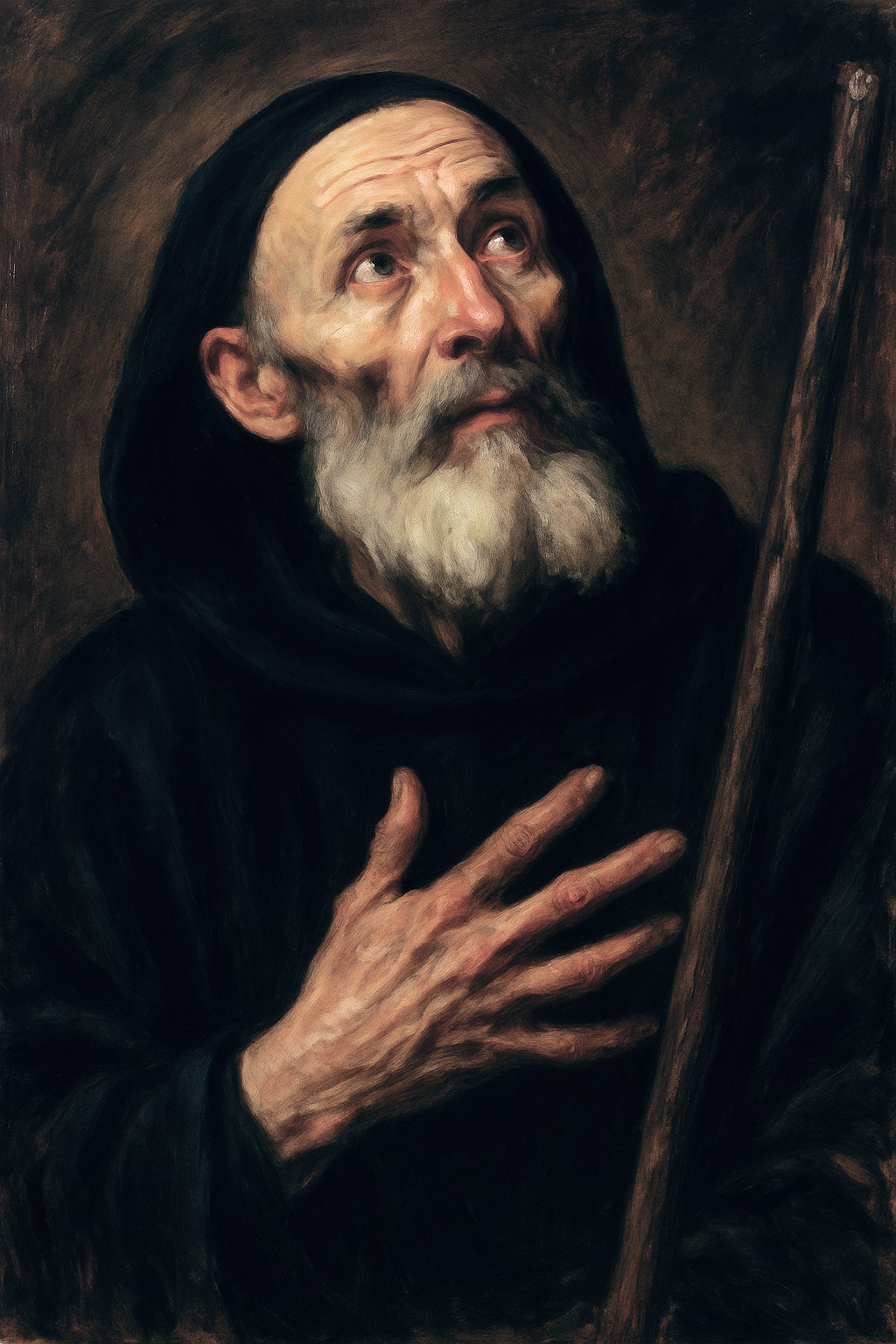

Saint William of Malavalle,

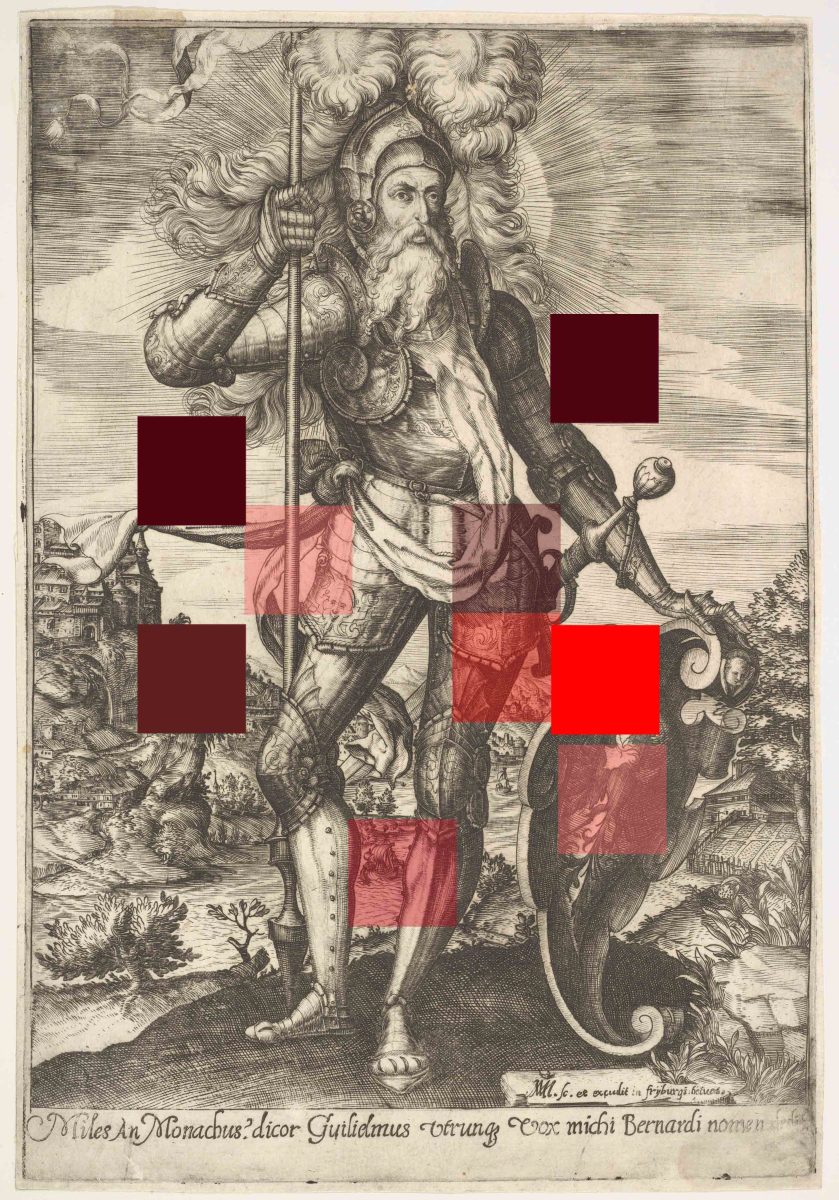

also known as William of Aquitaine (France – Castiglione della Pescaia, February 10, 1157), was a French-born knight who embraced the eremitic life. The early years of Saint William’s life remain shrouded in obscurity. According to a well-rooted tradition preserved in Tuscany, he was a French knight of noble lineage, said to be connected to the ducal house of Aquitaine and descended from the nobility of Poitou. He led a life of immorality and dissipation, and moreover supported the antipope Anacletus II; for this, he was excommunicated around the year 1136 by Pope Innocent II. According to tradition, it was Saint Bernard of Clairvaux who converted William — holding the Blessed Sacrament in his hands. Having completed the three great medieval pilgrimages — to Santiago de Compostela, Rome, and Jerusalem — he eventually arrived in Tuscany, where he embraced the solitary life of a hermit.

He made two unsuccessful attempts to reform eremitical communities according to his own strict ascetic discipline. Finally, he withdrew to Stabbio di Rodi, some eight kilometers from Castiglione della Pescaia, to a rocky valley through which a modest stream — the Ampio — flowed only in spring and autumn. The place, so remote that even hunters and shepherds avoided it, became known as „mala valle”, or “the wretched valley.” There, Saint William constructed a poor and fragile hut, in which he lived until his death on February 10, 1157 — first in solitude, and from the feast of the Epiphany in 1156, with a disciple named Albert. Shortly before his death, a second companion, Rinaldo, also joined them. In the solitude of Malavalle — which after his death became the cradle of his order — William embraced the monastic life he had always longed for. His way of life imitated, and perhaps even surpassed, the extreme asceticism of the Desert Fathers. Such rigorous bodily mortification is found only in hagiographic accounts and the classical literature of monastic asceticism. William observed continual fasting. He subsisted on raw herbs, water, and bread, brought to him from time to time by devout faithful from Buriano. He permitted himself warm food only three times a week and drank a small quantity of diluted wine; even on feast days, his diet remained unchanged. He reduced his intake of food and water to the bare minimum necessary for survival, so as to allow no indulgence to bodily desires. To his fasting he added manual labor. With his own hands he attempted to cultivate the barren soil surrounding his hut — a ground overgrown with thistles and brambles — so that even his work might become a form of divine service and penance. At night, he slept on a bed designed to prevent rest: he could neither stretch out nor lie comfortably. His head rested on a misshapen wooden support, and his body was pressed by coarse animal hides. At night, he wore a chain mail shirt directly against his naked skin. It is said that his body was covered with wounds and scars, by which he sought to imitate the suffering Christ. On February 10, 1157, in the midst of winter, William’s arduous and penitential life came to an end. Soon after his death, numerous devout pilgrims from Tuscany, Lazio, and Umbria began to visit his grave. Some of them chose to remain in Malavalle, embracing the eremitical and penitential way of life of the man they revered as their patron saint. His cult grew steadily in popularity, and on May 8, 1202, Pope Innocent III solemnly canonized him. Saint William of Malavalle did not found a religious order himself; rather, his teachings and example were gathered and preserved by his companion Brother Albert, who had joined him during the final year of his life and who subsequently established the Order of Saint William (the Williamites).

The hermit community grew rapidly. Following the foundation in Malavalle, monasteries were soon established in Tuscany, Lazio, and the Marche region. In 1244, the first communities beyond Italy were founded, and by 1256 the order had spread to northern France, the Low Countries (present-day Netherlands and Belgium), Germany, Bohemia, Austria, and Hungary. In the Kingdom of Hungary, King Béla IV initiated the foundation of Williamite monasteries. Religious houses were established in Körmend, Esztergom, Komár, Sáros, Harapkó, and Újhely, where the monks lived according to the Rule of Saint Augustine.

In 1256, Pope Alexander IV issued the papal bull Licet ecclesiae catholicae, formally establishing the Order of Saint Augustine. Within the framework of this "Great Union", several smaller eremitical congregations — including the Williamites — were incorporated into the new Augustinian Order. However, some Williamite monasteries refused to join the union, and thus a portion of the order continued independently. The cult of Saint William, along with his nearly unattainable model of penitential asceticism, was not confined to the Williamite Order alone. In 1314, for instance, the Hermits of Saint Augustine invoked him as an intercessor in the Gradual of their liturgy. Petrarch included him in his De Vita, among the exemplary hermits whose lives inspired contemplation and virtue. Yet the Williamites were not spared the tempests of history. By the end of the eighteenth century, scarcely any of their communities remained. By the end of the 18th century, only a few houses remained. The last Williamite monastery — in Huijbergen, Germany — was united in 1847 with the Cistercian Abbey of Bornem. On August 3, 1879, Father van den Berg died there, and with him the Williamite Order passed into history.

We, as contemporary Old Catholics, do not seek to return to the past, nor do we intend to revive the order in order to rewrite its history or to appropriate it. We live in an age that is dismantling its own Christian foundations and turning increasingly away from its religious heritage. Therefore, we desire to live our Old Catholic faith with evangelical integrity and wholehearted devotion, following a tradition that makes possible both a contemplative way of life and the service of our brothers and sisters with its spiritual fruits within the Union of Scranton.